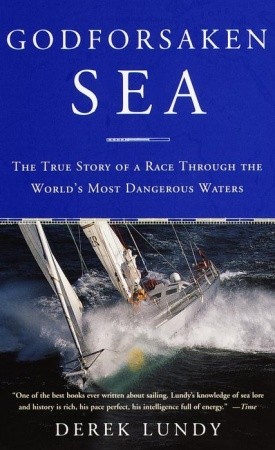

Illus. credit: goodbooks.com

(Beeler Large Print, Hampton Falls, NH, 1999, 323 pp.)

The vast sea area of the Southern Ocean is really the extreme southern portion of the Pacific, Indian, and South Atlantic Oceans. Its official demarcation is forty degrees south latitude. It includes the latitudes sailors long ago nicknamed the Roaring Forties, the Furious Fifties, and the Screaming Sixties. In storms, the waves build and build until they reach almost unimaginable heights. The largest wave ever reliably recorded, 120 feet, was encountered there.

The Southern Ocean contains that point on earth that is farthest from any land on earth. It’s about 1,660 miles equidistant from Pitcairn Island, the Bounty mutineers’ last refuge, and Cape Dart on Antarctica. Only a few astronauts have ever been farther from land than a person on a vessel at that position. But that doesn’t begin to describe the remoteness of this part of the planet. Some sailors call a large area of the Southern Ocean “the hole.” It’s too far away from even long-range aircraft to get to, conduct a rescue, and return to land. Ocean racing is inherently dangerous, yet a few have faced an even more extreme danger by challenging both their competitors and the Southern Ocean at once.

In the age of sail, racing was part of operating a successful commercial fleet. Square-riggers would load and race south on the Atlantic, round Cape Horn, and head for their markets in the Pacific. Those that arrived first could demand the best prices for their freight. Ship captains were reported to carry guns for the express purpose of shooting any officer, mate, or crewman that attempted to shorten sail even in the worst of storms. In 1905’s sailing season, for example, of the 130 square-riggers that sailed from Europe for the U.S. West Coast by way of the Horn, only 52 reached port intact. In history, one large Welsh shipping company owned 36 sailing vessels over the course of its business life. Twenty were declared wrecked or missing, and nine of them ended their lives off the Horn. At 20-30 men per ship, the numbers lost throughout the fleets mounted into the thousands and tens of thousands of souls lost over the years. Crew members rarely survived the loss of a ship. Further, if a man fell overboard, there was no recovery during the age of sail. Few knew how to swim, and even for those who could, all they and their crewmates aboard could do was stare at each other in shock as the ship charged on. Some of these ships were capable of such great speed that their runs went unmatched for well over a century.

In the infamous Fastnet Race of 1979, a 605 mile-long run from England to the Fastnet Rock lighthouse, eight miles off the southwest tip of Ireland, and back, a record 303 vessels set out. For 24-hours, the boats were raked by winds gusting to hurricane force and steep, breaking seas built to forty feet. Seventy-seven boats were completely capsized. Another hundred were knocked down at least once. Many boats lost rudders or suffered other serious damage. Several boats foundered. In spite of the largest peacetime rescue operation in British history, fifteen men died in the cold, rough seas.

The old sailors had a saying---”Below forty degrees south, there is no law; below fifty degrees south, there is no God.”

No comments:

Post a Comment